PRIMUS IN PROXIMO

Anatoly Osmolovsky

The Latin maxim Primus in proximo translates as “the first in the next (place), or “the first of the next” (time). This is an expression that I coined to replace the old-fashioned modernist concept of historical primacy.

Modernists zealously defended their priority in producing works that set the perspective for the development of art for many decades to come. The most obvious example is Malevich's Black Square. Why was priority so important to artists? First of all, art has been seen as a fundamental part of the historical process. The concept of time was introduced into art. Each moment in time could correspond to its own artistic form.

Postmodernism ruined this pattern, abolishing the concepts of primacy, originality and novelty. In the 1980s and 1990s, this abolition was seen as emancipation, a rejection of strict modernist discipline. All art forms have been renewed, even vulgarity and bad taste. However, along with this, we have lost the sense of time.

Reality was perceived as a bad infinity – no beginning and no end. And, in turn, postmodernism has become a burden. In fact, each generation lives in its own time. We should give a clear definition of the concept “generation.” A group of people born at the same time and experiencing similar social conditions, affected by the same historical and social events, is called a cohort or, more broadly, a generation.

So, the time of one generation is the “next time” – proximo if we use the Latin language. Here I am going to define when I was primus in my generation, in my proximo time.

Arbat. The first public performance.

At the age of 17, as a young poet, as I was walking down the first pedestrian street in Moscow, I saw poets reading poetry on the street, and immediately joined them. It was “Vertep” group performing for the first time on the streets.

At that time, the USSR banned any public performances for individuals without a special permission. “Vertep”, broke this rule, and this ban no longer existed. All summer and autumn 1987 the poets of Vertep performed on the street of Arbat. Practically, we were the only ones out there.

By autumn, other poets joined the core group. But by that time Vertep had become a social phenomenon. Newspapers started writing about us, TV stations reported on our performances, and finally they invited us to perform our spoken word at Yunost Magazine Day in Oktyabr cinema hall, the main cinema hall in Moscow.

Yunost Magazine Day featured live performances of poets, writers, rock bands, stand-up comedians, war veterans and labour heroes. It was a mishmash of various genres and styles, followed one other uninterrupted being introduced by the must-have emcee.

They would invite iconic poets and writers; rock bands would play a couple of songs, veterans would tell stories of their military past, stand-up comedians would make their audience laugh – it was a performance for every taste and, at the same time, it was completely tastelessness.

“Vertep” was also invited to read one verse at a time. I can’t remember how many of us performed, maybe two or three, or maybe just two of us. In any case, I was among the performers. I was dressed as a local punk (there were no real punk attributes – they cost mad money for a Soviet teenager), so I had to improvise: extremely short green work pants on huge suspenders with a shabby raincoat lining on top.

I had to read my own, rather scandalous text, inspired by Vladimir Mayakovsky. It started with the lines, “I am your voice, junkies and hookers.” It was a youthful, pretentious poem, but most importantly, I have outgrown it, I realized that it was superficial and sounded unconvincing. I no longer believed in this poem. At seventeen, you are growing up so fast, in three to four months you would be surprised at your recent stupidity, which seemed like an achievement.

At that time I started writing poetry in completely different styles, the aesthetics of futurism gave way to surrealism, complex metaphors, and verse libre.

And I would come on stage and start reading the texts that I was allowed to read (obviously, everything to be said on stage had to be approved in advance). However, it would be fair to say that my “approved” text was the most radical in terms of poetry themes and vocabulary), and, all of a sudden, I completely forgot my text. I stood there in a stupor. I couldn’t remember a single word.

I quickly made up my mind. I showed that this text had come to an end (it could have been interrupted in the middle), and started reading another poem, a freshly written surrealistic verse libre.

It seems really odd now, but practically no one in the USSR wrote verse libre. There was the Soviet poet Burich (now half-forgotten, but he was a good poet); they would immediately remember him, but no one else would (underground poets don't count, although even underground vers libre was not very popular). So, I read my verse libre and leave the stage.

Andrei Voznesensky would come up to me and say: your performance was really cool. Voznesensky was a prominent poеt of the “sixties” generation.

Voznesensky was like a rock band – he would gather crowds at the stadiums and read his poems in an incredibly sophisticated way, modulating his voice, shifting from shouting to whispering.

Perestroika was in full swing, and Voznesensky was one of those who wanted to renew the Soviet literature. The framework of so-called “socialist realism” (which he did not fit in) was perceived as iron shackles. Apparently, he saw in me and in the Vertep group some potential for these changes.

We – the Vertep group – arranged to meet Voznesensky in Peredelkino (a village near Moscow to host Soviet writers). To my shame, I did not read Voznesensky. I did not read any official Soviet poetry at all, and Voznesensky was part of extracurricular reading programme. I would throw to the bin everything recommended by the school (except for Mayakovsky).

Before we met I had read his second and apparently most successful book of poetry, “40 Retreats from the Poem Triangular Pear.” Surprisingly, I loved it. It was such a mannerist futurism: urban metaphors, alliteration, root rhyme, rhythmic interruptions. Unusually technically written poetry.

The meeting itself was not particularly remarkable. We read our poems. At that time, I wrote a text in line with the most popular Soviet slogan. The text was as follows: « Миру – мир. Мирумир. Мир – умир ». Voznesensky was very excited. At the time, he was making ’videomy" – that's how he called his short poems printed and exhibited in silk-screen technique.

I believe he did all of this with Robert Rauschenberg. The most famous “videoma” was “matmatma” printed in a circle. “Mat’”(mother) had been transformed into ‘t’ma’ (darkness). Well, my world fell apart. The simple transition of a letter from one word to another radically changed the meaning. I still consider this text to be quite successful. This is real poetic pop art.

But the poetic group “Vertep” did not become the phenomenon of literature, it was a social phenomenon which came in tune with Gorbachov’s idea of “glasnost.”

Ministry of problems of the USSR

After hours of debate, the Vertep group split up. The avant-garde members, capable of experiment, left the group, changed its name, and adopted new tactics. This is how the literary and critical group The Ministry of Problems of the USSR emerged. Apart from me, the group featured Dmitry Pimenov and Georgy Turov. Grigory Gusarov was a promoter and organiser of performances.

At that time, our texts were mainly read in various libraries, or student cafés. We left the streets. On Arbat Street, graphomaniacs would read their poems. There were crowds of them. They occupied every intersection of the street. Surprisingly, in the late 1980s, famous poets could easily fill a concert hall of 500 people. Gusarov was the one who organised such performances. Our prospects were much more humble. We couldn’t gather the crowd of more than 30 people on our own.

Our experiments went deeper and deeper into structuralism and the Tel Quel group. In 1986, they published a collection of manifestos from the major literary schools of the 20th century. It included André Breton's First Manifesto of Surrealism, Roland Barthes's text ‘Drama, Poem, Novel,’ and Ernst Jandl's manifesto of concrete poetry. In 1989, Roland Barthes' “Selected Works” was published. His essay “Mythologies” had a particular influence on us. It was the theoretical part, although the mythologies themselves — a series of short critical texts — were equally good.

At that moment, Dmitry Pimenov, a poet of our group, and I, formed a close creative alliance. It was Pimenov who came up with the concept of ‘likeness’ as a way to combat the myth. In short, it was formulated as follows: there was a myth about the avant-garde. These are scandalous, aggressive and outrageous artists and poets. In order to combat the myth, it must be embodied, i.e. we should become these scandalous and outrageous artists and poets ourselves. The myth, when it becomes reality, fades away and disappears.

The myth, according to Roland Barthes, was the main tool of social management by people in power. Therefore, it was necessary to fight it. In general, it was an idea close to simulationism, invented independently. However, it was different from simulationism in the absence of irony. Everything was completely serious. This is how postirony emerged, where the reflexive gap had been reduced to a minimum, or had been absent at all. In the Russian culture we were definitely the first in this role.

Left-wing radical ideology has always been the main provocative attribute. Most avant-garde phenomena of the 20th century were connected with it in one way or another. Roland Barthes and French structuralism were no exception. This connection ultimately had its own substantive meaning, since the idea of critical thinking supported artistic experimentation and the poetics of novelty. Therefore, our activity—the destruction of myth—naturally had to follow this path.

As a matter of fact, we took radical left-wing ideology as a ready-made, as a finished object, and installed it in the current artistic process, quite unexpectedly, one might say.

It was a big scandal! Of course, at that time, no intelligent person, no artist or poet would have associated themselves with leftist discourse in any way. It was worse than bad taste – it was unthinkable! Pimenov formulated another fundamental concept that served as a guide for me throughout my work in Russia: “an extra object is a symbol of truth.” Being superfluous, creating superfluous works, being always out of place—that is the true task of the modern avant-garde artist. That is how we understood it at the time.

At the same time, Pimenov wrote the manifesto “Terrorism and the Text” (given today’s realities, I would hesitate to publish this text again). This manifesto initiated a poetry evening in the café of the Moscow State University on November 18. Besides us, the event featured readings of Dmitry Prigov, Lev Rubinstein, and Yuri Arabov.

Each artistic ‘attraction’ of the perestroika era had its own ‘visit card,’ a technique, style, sound, or method that was unique to it. For example, Prigov would scream like a kikimora and read his poems so masterfully, with such obvious mocking intonation, that the audience would die of laughter. However, Lev Rubinstein, despite, or perhaps precisely because of, his stony impassivity, would bring the audience to paroxysms of laughter as he turned over his cards with brief remarks.

Our main recitation gig featured two “endless” texts. Dmitry Pimenov’s poem was “Forest, forest, hare, wolf bear” and mine was “One, one, one, two, three.” The first text was a monotonous reading of the word “forest” alternated with words “forest,” “wolf.” If you read this for a relatively long time, it’s perfectly natural to include the audience. She starts making up her own characters. That’s how a palm tree, a hippo, an owl emerged.

The predictability of my text was occasionally interrupted by the word “four,” the rhythm broke, and the possibility of further counting arose. The collective poetry recitation came into being. It was a real literature happening.

At the end of 1990, we organized a large screening of the French New Wave films with the assistance of the French Embassy in Russia. It took place at the Central House of Medical Workers. The Soviet Union had an extensive network of cultural centers, which were used for a variety of cultural events, including poetry readings, rock concerts, exhibitions, and film festivals. We titled our programme “The Explosion of the New Wave.”

We selected 14 films by various New Wave directors: Godard, Chabrol, Malle, Truffaut, Varda, and Marker. Some of them were presented to a wide Soviet audience for the first time. However, this was not a formal or commemorative event. Alongside the screenings, during the intermissions, various activities took place in the foyer: performances, poetry readings, screenplay readings, discussions, and public debates. All of this was in the spirit of Dadaist festivals. Two films were shown every day. The entire program would last two weeks. It would end with the screening of Louis Malle's film Zazie in the Metro.

At the end of this film, there is a theatrical fight in a restaurant in Charlie Chaplin iconic style. This fight was transferred to a real auditorium. Performers threw cakes at each other, cyclists rode across the stage, skiers ran around, and at the end, a real tame bear (hired by us along with a trainer) ran out. After dancing on stage on two paws for a few minutes, the bear ran into the auditorium, where it was met with a fearless audience. The media reviews of the festival were enthusiastic. All screenings were sold out. Until the 1990s, the attitude towards such risky ventures was overwhelmingly positive.

Actionism. Early 1990s.

On January 23, 1991, Prime Minister Pavlov's so-called confiscatory monetary reform took place. The essence of the reform was that the government wanted to completely deprive the population of the money they had on hand. They introduced new banknotes, and old ones could be exchanged at banks for only 1,000 rubles. People had only three days allowed for exchange. In April, prices for all goods rose threefold.

All this radically changed the atmosphere in society. Culture and art suddenly moved to the edge of public attention. Now we could no longer negotiate with the administration of the Houses of Culture on the distribution of ticket profits (for example, we earned 10,000 rubles at the “New Wave” explosion). Under the new economic conditions, the administration demanded 100% prepayment. Therefore, only wealthy promotional companies that were mainly involved in so-called “pop music” could carry on their gigs.

In 1991, the USSR clearly began to “tighten the screws,” as people said when they wanted to express that reforms were being rolled back and democracy was being abolished. In April, the so-called “morality law” was passed. It prohibited swearing in public places. This became a reason for us to stage a street protest. We already had a similar experience. During the “New Wave Explosion,” we filmed a scene with people eating sausage in front of the Mausoleum on the Red Square with an amateur camera.

The film never got made. It turned out to be unfeasible both financially and logistically (video was extremely rare at the time, and we were shooting with film). However, in 1991, I decided to stage a real protest: to spell out the word “fuck” with the bodies of activists in the Red Square. This was our response to the new law on morality. Red Square was a so-called “restricted area” under special protection and with certain rules of conduct. For example, under the Soviet rule, smoking was prohibited in the Red Square and, of course, no rallies were allowed.

The event was scheduled for April 18. Only three people showed up for the main meeting: two young art historians, Alexandra Obukhova and Milena Orlova, and one anarcho-syndicalist, Max Kuchinsky. Besides me, the organizing group included Grigory Gusarov, our longtime promoter. He was supposed to distract the police. We didn't have enough people. According to my calculations, we needed thirteen people. We went to the gathering places of the so-called informal youth, punks and hippies. There, I encouraged them to take part in the action. We managed to gather thirteen people, including myself and Gusarov.

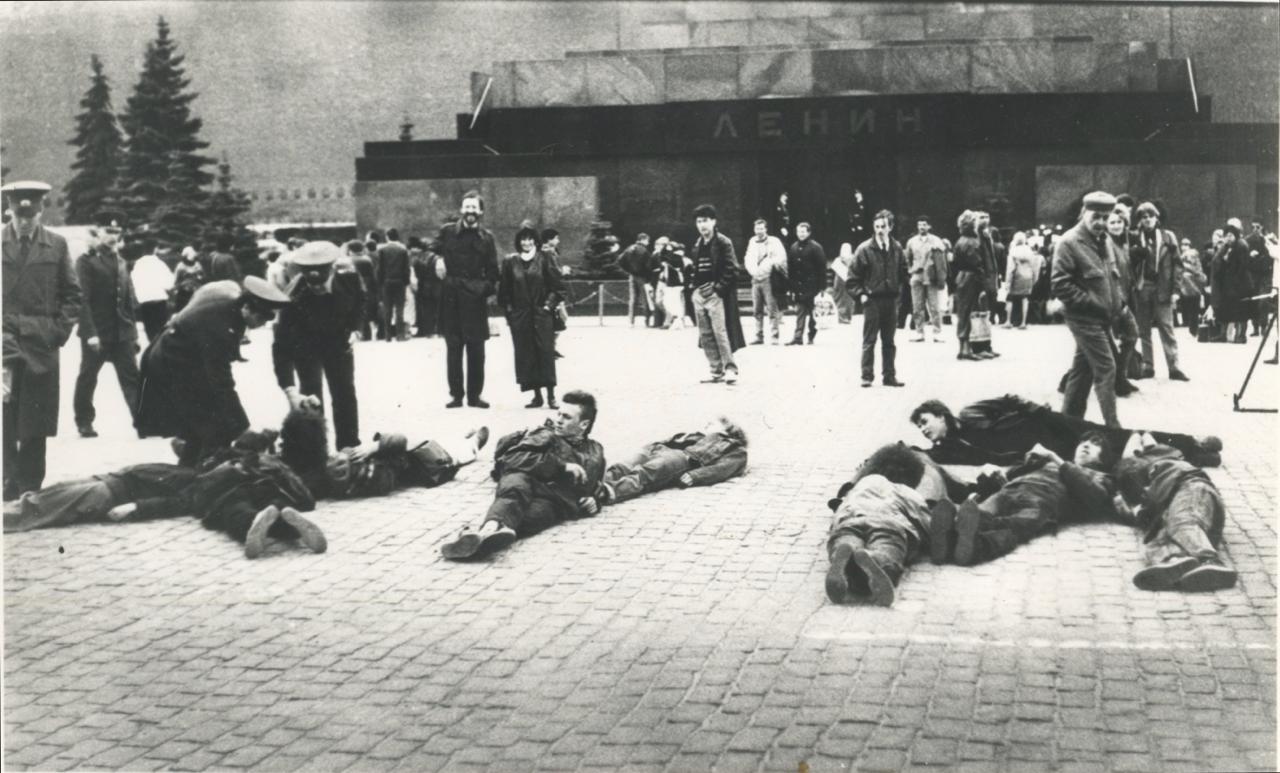

«E.T.I. - TEXT» (popularly – «ХУЙ», which means “dick”), 18 April 1991, Moscow, Red Square in front of Lenin’s Mausoleum

So, we went to the Red Square. In the first letter, “X,” there is art historian and anarchist Max and some punk. But when we came to the Square, people just froze. Everyone was very scared. I literally had to place people on the square with my own hands, like sculptures. I lay down on the last letter, “Y,” myself. And the line above the letter was a random passerby—a young man whom I called from the cobblestones of the square. Despite the fact that Gusarov distracted the police, they immediately rushed to the people lying on the ground and began to lift them off the square. People actually lay there for about 30 seconds. I managed to take only two shots.

At the police station, we said that we were laying out geometric shapes. After establishing our identities, everyone was released. In the evening, Gusarov showed me a photograph and asked: shall we publish all of this in Moskovsky Komsomolets? At that time, the newspaper had a huge circulation of 1.8 million copies. I said: “Called a mushroom — climb into the basket.” (A popular Russian saying meaning “do what you have to do, and then we'll see,” or “live up to the calling you have chosen for yourself”).

The next morning, right after the morning edition of the newspaper hits the newsstands, the police arrive at my apartment to conduct a search. A criminal case was opened under the legal article “hooliganism committed with exceptional cynicism and particular audacity,” punishable by up to five years in prison. I am probably the last person who spoke with the KGB agents. People were lying right in front of Lenin's Mausoleum, on which the leader's name was written. The KGB was interested in whether I wanted to associate the word “dick” with Lenin's name. The poet Voznesensky advised me to reply that, in line with the spelling rules, if I wanted to associate the two, I would have used a hyphen. The action had a huge impact.

It was used as an argument at various CPSU party meetings that all reforms should be rolled back now that this had become possible. But the cultural community stood up for us. And literally three days before the August 1991 coup, the case was closed due to lack of evidence.

I am considered the founding father of street actions, gestures, and performances. In fact, street actions were rare in the history of the Soviet underground, but they did happen. For example, the group Collective Actions held an action called Group 3, in which several people stood on the street with two banners, one reading “group” and the other reading “3.” Or, the group Mukhomor had an action in the Moscow metro, staying there from opening to closing. According to the agreement, anyone who wanted to could meet them at predetermined stations. However, none of these actions were intended to be made public. This is understandable, since under the Soviet rule, any action that attracted the attention of the press was almost automatically considered a criminal offense. On the other hand, my actions, were designed to elicit a reaction from the mass media.

I would deliberately choose iconic forbidden places, desacralizing urban space. So, my main “discovery” was a direct connection between public gestures and the mass media.

In 1991, we staged a few more actions. Such practices were completely unknown to the Soviet press. And often I had to explain some basic truths of Actionism to the press. By the way, the group that carried out all these actions was called “Expropriation of Art Territory,” abbreviated as the ETI movement.

The ETI movement was an attempt to create a youth movement. It was not successful. Everyone knew about the ETI's actions, but at that time no one else was using this practice. The original idea was to spark a mass movement. Such activities became popular among artists and young people much later, in the 2000s. The actions of the groups Voina (The War), Pussy Riot, Pavlensky, Krysevitch, Verzilov, Nenasheva, among many others were engaged in a different era, in post-perestroika Russia.

In 1993, I staged another solo performance. I climbed onto the shoulder of the Mayakovsky monument. The performance was called “Nezesudik’s Journey to the Land of the Brobdingnags.” The Brobdingnags are giants in Swift's novel Gulliver's Travels. And “Nezesudik” is the name of a new collective project I organized in 1993. This time, only artists took part in it. The word “Nezesudik” itself was translated from Volapük, the most unused but first artificial language, as “superfluous.” Superfluous in the most superfluous language in the world. The title of my action referred to the futuristic practice of word creation and the abstruse language of the Russian futurists.

Titles play an important role for me. Sometimes they are as important as the art work itself.

In 1994, I published the first issue of the art magazine Radek. It was a truly avant-garde magazine that published a variety of texts: poetry, prose, and theory. In total, four full issues were published throughout the years. The last one was no longer titled Radek. It had no name at all. It simply bore the number N. It was dedicated to left-wing terrorism in Germany and Italy in the 1970s. Many people were interested in the topic, but few dared to explore it.

Many other online projects are associated with Radek. There was Mail-Radek, which sent short and not-so-short texts reflecting on the current artistic process to several hundred subscribers over a period of two years. In 1997, social media did not yet exist, so the editorial team would use regular e-mail correspondence.

We published Hendradek – a small leaflet produced by a group of young activists my students and those of Avdey Ter-Oganian. In the end, these activists took the name of the magazine, Radek, as the name of their group. So, with a touch of humour, one could say that the magazine ultimately came to life and everything written in it was realised in real life. The Radek group practiced a variety of experimental activities, simultaneously merging art with the organization of exhibitions. For example, they opened their own exhibition space, Galerie France).

1998-2000, “Against All” Campaign. The presidential and parliamentary election campaign.

From 1995 to 1997, I worked on various election campaigns as a political manager, organising demonstrations, writing propaganda materials, and editing politicians' speeches. It was a paid job, but in addition to getting money, I gained experience and learned the intricacies of the political process (if the chaos of that time can be called that). By 1998, I approached the new election cycle (the 1999 State Duma elections – the Russian parliament – and the 2000 presidential elections, in which, incidentally, Putin was elected for the first time) with a global idea of ‘against all’. The fact is that, under the electoral law at the time, in addition to the registered candidates on the ballot, there was a column marked ‘against all.’ In other words, voters could choose not to cast their vote for anyone, but instead vote against all candidates. Moreover, this option was included in the ballot from the outset, and voting for it did not require registration or the collection of any supporting votes for this registration. In short, it was an action completely free from any contact with the state system. As for the candidates, there was no doubt that the ballot papers would feature repulsive pseudo-parties, each worse than the other. The ‘democratic’ parties were usually tiny, and were called the ‘Garden Ring’ parties (it would mean that their influence was so insignificant that it did not extend beyond the Garden Ring in Moscow – the first ring road after Red Square and the Kremlin), and they usually had the most talentless and deceitful political campaigning. Political managers, knowing how ‘far from the people’ they were, came up with pseudo-folk election clips with folk songs, balalaikas and other cringe-worthy nonsense (this was done by Yavlinsky's Democratic Party).

Another option was the Gaidar-Chubais party, which made its videos in the cabin of an aeroplane flying over Russia – also cringe-worthy, but detached from reality. Communists, nationalists, all the sorts of social climbers, or simply mafia gangsters who invented parties for the elections in order to obtain the coveted mandate—none of them represented any alternative and were generally insignificant. Therefore, the idea of voting against all seemed extremely promising to me. In addition, I saw in it a political expression of the ideas of Deleuze and Guattari, material for theorising, for new activist practice.

In 1998, I established a group “the Non-Governmental Control Commission.” This group featured artists, political activists, and theatre figures. The main thing was to create a real organization. If fifty active people joined such an organization, it could, strange as it may seem, represent a serious force.

In May 1998, the Non-Governmental Control Commission hosted its first event – built up a barricade on Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street in memory of the May 1968 events in Paris. It was the largest event in terms of participants initiated by artists.

About 300 people gather and we blocked traffic in the city centre for several hours. It was a kind of re-enactment of a new genre of contemporary art that was just emerging at that time. The most important thing about the action was that all the slogans were in French, repeating the slogans of 1968, and the main activists on the barricades were mainly French students. At that very moment, students from Grenoble School of Contemporary Art arrived to meet with Avdey Ter-Oganian, a member of the VPKK. We handed them the megaphone at the barricade. Most of the speeches were made in French. The police officers who had gathered there could not understand what was happening. A couple of hours later, as soon as the demonstrators left the site and tried to march down the street, they were all detained. But a few days’ detention and a small fine were a perfectly adequate response by the authorities to what was, in its essence, a harmless and cheerful event.

A completely uncontrollable factor intervened in the election campaign. The authorities could not understand who these people were. What were their goals? Who hired them? Who covered them? The Federal Security Service was orderedd to stop our activities. All our assets were put under phone surveillance, and our second, completely harmless action – we wanted to put stickers on the toilets in Manezhnaya Square with the words “Ballot boxes. Vote against all!” was interrupted by the FSB. The persecution continued to escalate. Some activists were subjected to psychological pressure (imagine being followed by several days by people who changed every eight hours, keeping a distance of a couple of metres), while others were brutally beaten by specially sent “hooligans.”

We had the presidential election the next year. There were the very elections in which the President Putin was elected for the first time. The activity of the non-governmental commission no longer had the element of surprise.

The authorities feared that when voters would be faced with a choice between the communist Zyuganov and the former KGB officer Putin, they would prefer to vote “against all” and thus Putin would lose votes. Therefore, a special group was formed to engage in counter-campaigning.

Its task was to create an unattractive image of the candidate against all. For example, homeless people were hired and forced to sit on the street with posters saying “Against all.”

They would interview drunk homeless people and show them on TV. To be honest, we watched all of this with amusement. Well, it’s really fun when the authorities fight a non-existent threat and try to put on a show themselves.

But overall, once I came under the FSB’s scrutiny, it was clear to me that this whole line of action had reached a dead end. The forces were too unequal, and there was no interest from real organisations, even small ones. None of them saw the point in campaigning “Against all”.

What does art have to do with it? Indeed, there is practically no art here, except for the generally cheerful and creative approach to the election campaign itself. However, I viewed this entire project by the Situationists’ idea: ‘We are artists insofar as we are NOT artists. We have come to bring art to life. That is, as the most extreme form of art that dialectically removes art itself.

Nonspectacular Art 2000–2003

In 2000 I was invited to the periodic exhibition Manifesta 3 held in Ljubljana. I often took part in different biennials. In 1993, for example, I was at the Venice Biennale — the youngest participant in its history (I was 22). True, my “record” was broken at the next Biennale by a 19-year-old artist. I also took part in the Istanbul Biennale, the São Paulo Biennale, and the Valencia Biennale. The 2000s were the years when numerous periodic exhibitions began to emerge. Manifesta had set this trend back in the 1990s.

At Manifesta I presented the following work: I proposed to lower an artillery gun into a manhole as a symbol of the end of war. Although Slovenia avoided civil war, as part of the former Yugoslavia it still related to it, at least as a witness. I solemnly titled the work “Monument to the Splendid and Victorious NATO General Dr. Freud”, since the war had been brought to an end precisely by NATO’s bombing of Serbia.

What interested me most in this idea from a formal, artistic point of view? The gun, turned upside down and stuck barrel-first into a manhole, became a modernist sculpture in the spirit of Anthony Caro. The artillery piece on its carriage had split trails, and when spread apart they resembled an open flower. I was also intrigued by weapons as sculptural objects. Later I would create several more works on this theme. As the Soviet underground artist Mikhail Chernyshov once aptly put it, Soviet pop art could only be connected with the army, since it was the only respected consumer in the USSR. In other words, armaments were the only things worthy of an artistic response.

That Manifesta was brilliant. Although no more than thirty artists were invited, it presented radical works. A couple of days before my departure I was sitting in a café near the hotel, speaking Russian on the phone. A man approached me and spoke Russian as well. It turned out to be Paweł Althamer, a well-known Polish artist and participant of Manifesta. He told me that in the center of Ljubljana, in the main square, there was an almost unnoticeable performance taking place daily: an old man fed pigeons, an intellectual sat in a café reading Baudrillard, rollerbladers skated through, and at a certain moment a young man and woman met for a date. But none of this was real life — all the “characters” were hired actors. This work amazed me. I suddenly realized that an artwork did not have to astonish the viewer; it could disguise itself, mimic ordinary life, or become almost indistinguishable from it.

I must say that we had once done something similar during the screening “Explosion of the New Wave” in 1990. While François Truffaut’s film was being shown, the lights came on twice, interrupting the film. In the audience sat a young man who imagined he was making love to a woman sitting in the hall. This was the idea of Dmitry Pimenov and was called “the art of presence.” But at that time (and even now) Russia lacked institutions capable of registering such elusive works.

Returning to Moscow, I began to promote nonspectacular art. The name came naturally, adapted from the phrase “nonspectacular forms of dramatization” used by Catherine David at Documenta X.

At the annual Art Moscow fair, Roger Buergel (future curator of Documenta 12) curated the exhibition “Subject and Power (the Lyrical Voice)”, where I presented several nonspectacular works. For example, Critique of the State of the Walls — a wooden panel painted white and placed leaning against the wall of the Central House of Artists.

But the programmatic exhibition took place right after the fair closed. For two weeks the booths of all the galleries were given over to artists. This event was called “Art Moscow Workshops”. Each artist received a gallery booth and could exhibit whatever he wanted — there were no curators. I developed a project I called “Imposition” — in contrast to the traditional “exposition”.

At the official opening, my booth displayed a notice announcing that the opening of my exhibition was postponed until the next day (that is, when there would be no journalists or television, only those genuinely interested in art). Next to it was a small manifesto protesting against “obscene visibility and mass-media solicitation,” written in the characteristic jargon of the Situationists.

The next day the “imposition” was opened: in my booth hung only a single list of works, while the works themselves were dispersed throughout the exhibition (not in others’ booths, of course, but in the passages between them, on the walls, and in the corridors).

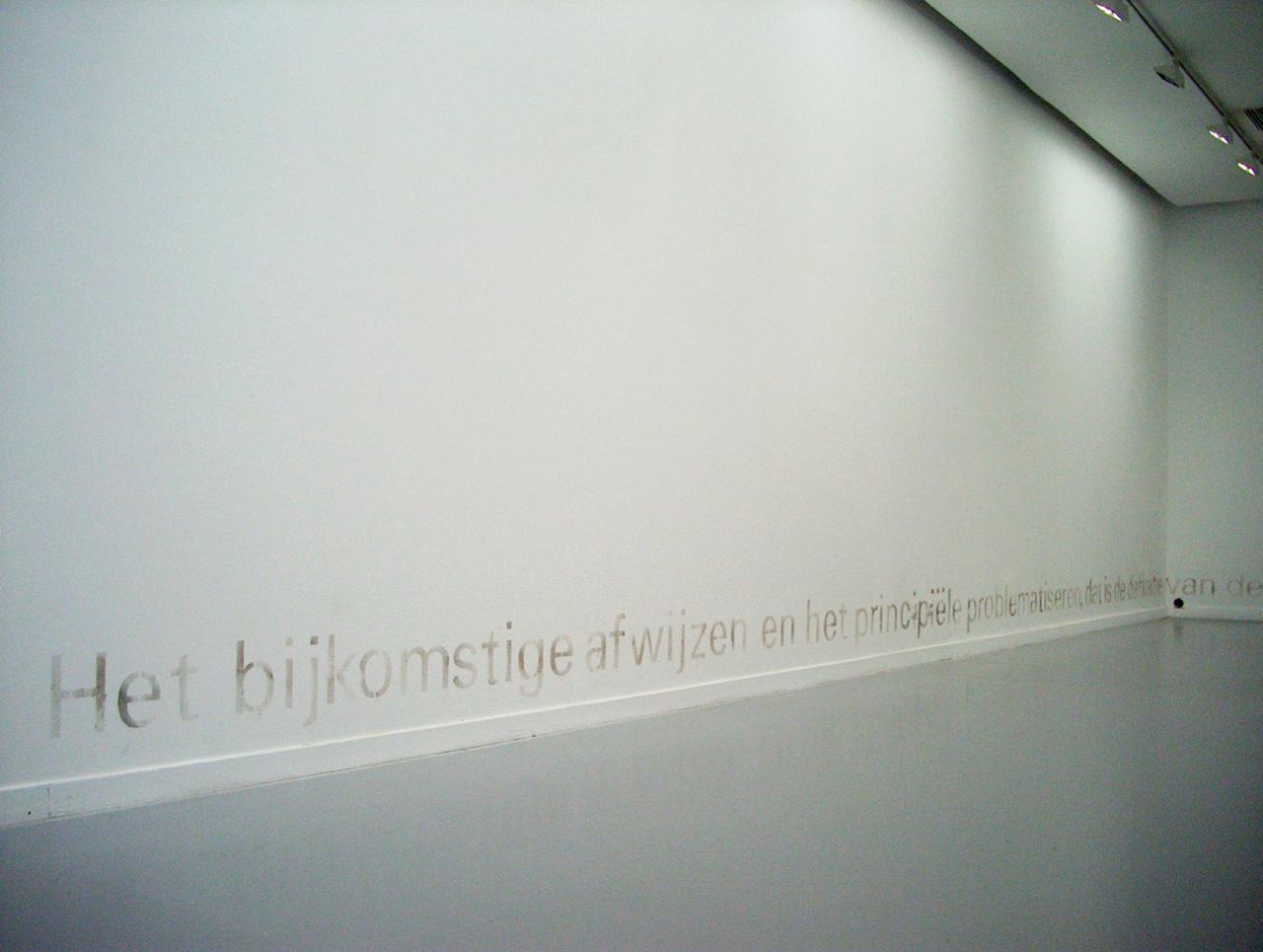

“Folded Flags and Unread Books” — red banners folded in a corner and a stack of books by V. Lenin and K. Marx, covered in dust. Later this piece became the basis for a more “refined” nonspectacular work, “Dusty Phrases” — a series of my own statements traced in dust along the bottom edge of the wall.

“No Future for You”. In one passage stood what looked like an ordinary metal bucket of water with a mop and rag beside it. Yet the bucket had a double bottom with a hidden speaker quietly playing a fragment of the Sex Pistols’ song with the words “No future for you.” When the music played, ripples appeared on the water — if you looked closely, you could notice them.

“Arise, ye wretched of the earth…” I removed one floorboard and replaced it with another made to look as if it had exploded and one splintered end was rising upward.

“Blood & Perfume”. Several milliliters of blood were splashed on the wall and generously doused with perfume.

It is telling enough that all these works did not last long. The next day my floorboard was removed, the blood and perfume were wiped away, and even the books and flags were carried off. Although everything had been agreed with the administration of the exhibition hall, the workers and guards had not been informed and interpreted all these interventions as hooliganism. A kind of “popular” censorship.

New Formalism 2004–2007

By the mid-2000s the idea of nonspectacular art had exhausted itself.

First, it became very popular in professional circles, mainly among young artists. This was understandable: such works did not require large financial investments and were usually based on artistic wit and a playful approach.

Second — and this was the main factor — an art market appeared in Russia. Still in its infancy, yet private galleries, foundations, and museums were growing exponentially. Competition arose between them, and with it, the ambitions of owners and their desire to influence the process. The annual Kandinsky Prize was established, with a large cash award, a major preliminary exhibition, and a ceremonious award ceremony. All this was new. It seemed to me that this segment was the most interesting. New people, new relationships, and therefore new opportunities for experimentation and research emerged within it.

I began to work with the Stella Art Gallery and Foundation. My first exhibition there was titled “How Political Positions Turn into Form”. This exhibition opened simultaneously with the First Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art. What did I want to show? I wanted to demonstrate that my political positions had their own visual expression — abstract, in the form of pure shape without any explicit political content. Probably the most striking works in this series were enlarged forms of my fingernail clippings, as well as a single toenail that I had grown for two years. Here it is worth noting that I was interested in objects that usually lie at the edge of our visual perception, that are felt by the hands: bread, nail clippings, nutshells, metro tickets.

The best-known works of this period were the “Products” — a series of bronze sculptures whose forms reproduce the armor of modern tank turrets. These turrets were stripped of artillery barrels, mounted machine guns, and other military fittings. What remained was the pure form of the armor plate itself. The title of the work was an inversion. In the Soviet and Russian military-industrial complex, all newly tested prototypes were conventionally called izdeliya (“products”). Once adopted into service, they were given a number and a proper name. By making these sculptures, I returned them to the category of products — but now they were no longer the products of the military-industrial complex, but of art. After all, art also produces products!

In 2007 I received my first Kandinsky Prize as Artist of the Year. At the exhibition of nominees, the “Products” were shown alongside another work that became very well known (in fact, an entire ongoing cycle), titled “Breads”.

“Breads”. Iconostasis. Auratism 2007–2012

In the mid-2000s I became deeply fascinated by ancient Russian icon painting. My interest was purely aesthetic. As an atheist, I had never been particularly drawn to this art before, but suddenly I discovered it for myself. I wanted to bring certain iconographic and Christian codes into my own art. The result was my first bread iconostasis.

It should be said that I spent two years trying to solve a technical problem: how to reproduce the texture of a slice of bread without losing visual realism. It so happened that at that very moment CNC machines (computer numerical control) first appeared in Russia’s civilian sector. They solved the problem perfectly. But the coincidences did not end there. In 2007, as I was making my first iconostasis, Oleg Kulik decided to organize an exhibition in the newly opened first Moscow art cluster Winzavod, with the then-scandalous title “I Believe”. Scandalous, of course, for the professional art community. Since 1998 there had been sharp conflicts between contemporary artists and the Orthodox Church, ending with smashed exhibitions, lawsuits, even criminal prosecutions. Attitudes toward faith, especially overt religiosity and clericalism, were generally skeptical.

But Oleg Kulik had never shied away from going against public opinion. The exhibition “I Believe” opened. And, remarkably, my iconostasis was ready just one day before the opening. It became a “blockbuster” there. The exhibition as a whole was extremely popular: on the first day alone it attracted 30,000 visitors. Long lines stretched outside.

2007 was also the year of Documenta 12. The coincidences continued: during the run of the exhibition “I Believe”, Roger Buergel, the chief curator of Documenta, came to Moscow. Seeing my iconostasis, he exclaimed: “This is exactly what I need!” That was how the work made it to Documenta.

It should be noted that Soviet underground art of the 1960s and 1970s was closely connected with religiosity. This was understandable: in the USSR religion was not encouraged, the official ideology was atheistic, and many underground artists, in protest and in search of an independent platform beyond ideology, turned to religion. This was reflected in the forms and motifs of their work. Perhaps the most famous and interesting was Mikhail Shvartsman an artist who called himself a hierat and his works hieratures. In fact, these were abstract forms created using icon-painting techniques. Another artist, Eduard Shteinberg , used Malevich-like geometry to create a similar effect of elevated spirituality. The next generation of conceptualist artists ironically labeled such work dukhovka (“spiritual oven”). At some point all this “spiritualism” became, if not kitsch, then at least a rather pretentious pose.

That is why some critics, curators, and artists, knowing my background, reacted very critically to the iconostasis at “I Believe”Andrei Kovalev wrote a scathing review, accusing me of renegadism, reactionary positions, and religiosity. Others rolled their eyes and insisted that this work must by no means be shown to Roger Buergel.

But my idea was entirely different — indeed, the exact opposite.

First, I wanted to show that “spirituality” (I called it auratism, from Walter Benjamin’s famous term “aura”) is an artistic effect. There is nothing mystical or religious about it. By using a set of techniques, one can create an aesthetic regime of “aura.” Technical reproducibility is not an obstacle for “aura,” since all these works were made with digital technology and could be repeated in any number of copies. One might even say that, in a sense, the “Breads” were a parody of Shvartsman’s hieratures.

Second, I sought to demonstrate that everything attributed to church art is created by artists, possesses aesthetic value, and that “spiritual” meaning is generated by artistic means. By reconstructing the iconostasis order and employing Christian codes, I created an art object that in fact contained no religious content. As proof of this resounding absence, I used the same texture, altered the form, and made art objects with the directly opposite, “pagan” content — totems of an unknown cult. At the 3rd Moscow Biennale, curated by Jean-Hubert Martin, one such totem was exhibited.

The problem of the uniqueness of an artwork, its copy, and its mass reproducibility fascinates me deeply. In today’s era of digital content it is often said that uniqueness has vanished as a fact. The whole world, they say, consists of simulacra — copies without originals. The means of copying have reached extraordinary quality; some even claim that the texture of an artist’s brushstroke can now be reproduced. All this seems true. But a copy faces two extremely important ontological obstacles.

The first is space. The original occupies a specific place in reality; no matter how perfect, the copy occupies another place — and in this lies their irreducible difference.

The second, no less important, is the time of creation. The copy always arises after the original. The original and the copy are not equal in time. Moreover, a copy of a copy can differ by its own time of creation. If we take these two aspects into account, we could even claim that the world consists exclusively of originals, and that copies hardly exist at all. Of course, one can try to create a copy without an original inside digital reality. But to do this one must make a special effort, invent a protocol that instantly replicates a created original in a multitude of copies. Yet even inside virtual reality, each will still occupy its own place.

In my view, this problematic has real potential for the development of art, for the creation of new forms, and even more — for a new worldview that could overcome postmodern indifference.

Sarcastic Art 2012–2015

At the turn of the 2000s and 2010s, Russia stood at a crossroads. In 2008 Dmitry Medvedev became president, and his term ended four years later. As is well known, in 2012, during the presidential elections in Moscow, when Putin returned to replace Medvedev, a mass protest took place. Well, “mass” is relative: never more than a hundred thousand demonstrators gathered, which is not much for a city of ten million. The overwhelming majority of protesters held liberal views, and so the protest took on a moderate character. Nobody pushed for escalation. The campaign itself was conducted extremely sluggishly, without clear plans or goals. At times the main issue was said to be the presence of Lenin’s body in the Mausoleum on Red Square. People repeated: “Until Lenin is buried, nothing good can happen in Russia. There’s a corpse lying at the country’s center!” This kind of magical thinking, for me personally, could not serve as the basis for any serious reforms.

It was then that I conceived of creating a series of sarcastic works whose outward appearance met the expectations of the public, but whose meaning was the exact opposite. The first work was a series of sculptural portraits of dead revolutionaries. In general, the theme of revolution was far removed from the context of the time. Liberals could not stand it. Accordingly, these portraits of revolutionaries became genuine “superfluous objects.” When I modeled Lenin’s portrait, I was absolutely certain that nobody in Russia was doing such a thing. As for portraits of Trotsky or Bakunin — needless to say, they were half-forgotten figures of interest only to historians.

In the end, I identified three revolutionary stages: the 19th century — Marx, Engels, Bakunin; the Russian Revolution — Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin; the revolutionary situation of the 1960s — Mao, Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh.

My choice of figures followed the scheme: founder – continuer – opponent. All these portraits — bronze sculpted heads — were meant to be exhibited on poles, clearly creating the impression of decapitated enemies or defeated criminals put on display. The key lay in the title. The work was called: “Did You Do This? — No, You Did This!” The main intrigue of the work was in the catastrophic imbalance between its parts — the bronze heads and the literary title.

The title consists of words attributed to Picasso. According to an apocryphal story, a German officer, after seeing the painting Guernica, asked Picasso: “Did you do this?” Picasso shifted the conversation from art to reality, answering about the actual bombing of the city of Guernica by German aviation, which took part in the Spanish Civil War on the side of the Francoist rebels.

But what meaning does this question-and-answer have in relation to my work?

In Russia there is a persistent belief that contemporary artists possess no traditional artistic skills. That they cannot draw or sculpt. That they do not understand paints or materials. That they order everything from “professionals” and then exhibit it under their own name. In my case, there was even a journalistic investigation into how much I actually participated in the making of my works. Therefore, I recoded Picasso’s question as one addressed to me: “Did you do this?” — meaning, did you sculpt these heads yourself, with your own hands? And the answer is decoded as: “No, you did this!” — that is, you were the ones who cut off the revolutionaries’ heads, you were the ones who put them on display, as in the Middle Ages!

And indeed, most people enjoyed the spectacle. The majority ignored the sarcastic meaning of my work.

Institute “Baza” 2011–2024. Emigration

In 2011 my wife, the film director Svetlana Baskova, and I founded an independent private educational institution called Baza. The course of study lasted two years. I taught the history of contemporary art. We became the leading educational institution for contemporary art in Russia. Every year until 2024 about thirty students graduated from Baza. Each year we also held a major graduate exhibition. But we also pursued scholarly activities: we organized round tables and conferences and published the almanac Baza, and later the journal Termite. The second issue of the Baza almanac consisted entirely of materials from the French journal Tel Quel, compiled and introduced by Jean-Pierre Salgas. We translated and published works by Philippe Sollers, Denis Roche, and Pierre Guyotat.

In 2013, within the parallel program of the Venice Biennale, the VAC Foundation of Moscow organized a large joint exhibition of mine with Paweł Althamer. For me it was a partial retrospective showing my key works. Althamer, on the other hand, presented a project centered on video documentation of altered states of consciousness — from various narcotics and LSD to the so-called “truth serum.”

Of course, there were great plans for that decade, but they were not to be realized. In 2014 came the annexation of Crimea. The majority of Russian society experienced something like narcotic ecstasy. The art community that had taken decades to build began slowly but inexorably to disintegrate. The political climate in the country changed radically.

Because our educational institution was in no way dependent on state funding, we managed to stay afloat for quite a long time. The laws gradually tightened, but we avoided self-censorship and followed artistic logic in the creation of exhibitions and works.

On 24 February 2022 Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. For me it was a shock and, at the same time, a surge of anger and indignation, so absurd and unmotivated was this aggression. From the very first day I began publishing antiwar posts on Facebook. My first suggestion to Putin was that he voluntarily present himself before the Hague Tribunal. That would truly have been a nontrivial historical gesture.

Having been raised under Soviet power, our ultimate nightmare was nuclear war. So when Putin began blackmailing the world with the threat of a nuclear strike, it filled me with disgust. With such a person there is nothing to discuss. I consider Putin to be an absolute consumer, a hedonist pushed to the point of self-negation. Hedonism and war incompatible? Only at first glance. For Putin war is “dvizhukha” (his own word — “action, a happening”), a game of toy soldiers, a remedy for boredom, the final entertainment. And the only emotion still connecting him to reality is the fear of his own death. Only through this emotion can one speak with him.

On 23 March 2024, at six in the morning, an FSB squad burst into our apartment with a search warrant. With assault rifles they forced my wife and me face down on the floor. To be honest, I found it funny. Funny because when the force of the blow does not match its target, it looks pathetic — excessively theatrical and strained. I was suspected of “treason against the Motherland” without the slightest grounds. At the same time searches were carried out at the homes of thirty artists and curators in various Russian cities. In total there were about ten FSB agents in our apartment. A simple calculation shows that more than 300 specially trained professionals were deployed just for these searches. And three days later the terrorist attack took place at Crocus City Hall, where the terrorists were met by a single unarmed security guard. One hundred forty-nine people died in that attack. That is all one needs to know about the efficiency of the Russian state.

The day after the search we left Russia.

Despite our emigration, the educational infrastructure and faculty remained in Russia, and we cherished the illusion that we could continue the educational process. We were cruelly mistaken. Announcing a new admission campaign in the summer of 2024, the very next day the faculty of Baza and even some of our friends — some of whom had nothing to do with the Moscow art scene — were subjected to searches. Our case was reclassified from “treason” to “drug trafficking” (the standard article used when there is nothing else to charge). Baza had to be closed.

Now, having found refuge in the West, a new life is beginning for us — life after death, or life in “the other world.” Once the philosopher Boris Groys formulated the idea that Russia is the subconscious of the West — that in Russia the West’s fantasies, which had no chance of being realized in the “metropolis,” were played out. This idea fit quite well with the Soviet communist experiment. But today Russia has no plan for the future, no ideas at all. On the contrary, it is trying to stop all processes of thought within itself. Does it still remain the West’s “subconscious” in that case?

Translation : Anna Likalter

Photo:

«E.T.I. - TEXT» (popularly – «ХУЙ», which means “dick”), 18 April 1991

“Nezesudik’s Journey to the Land of the Brobdingnags”, 1993, Moscow, Mayakovsky Square

“Barricade on Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street,” May 23, 1998

“Against all”, 1999, Moscow, Red Square in front of Lenin’s Mausoleum

“Monument to the Splendid and Victorious NATO General Dr. Freud”, 2000, Manifesta 3, Ljubljana, Slovenia

“Dusty Phrases”, Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp

“Arise, ye wretched of the earth…” , 2002

“How Political Positions Turn into Form”, Stella Art foundation, 2004

Iconostasis (“Breads” series) from the exhibition “I Believe”, 2007

Totem 2009